By Argentina specialist Melissa

Ruta 40 is the definitive great Argentinian highway. Rather like the USA's Route 66 and Jack Kerouac, it has a legendary status as the stomping ground of a young, road-tripping Che Guevara.

It runs down Argentina’s western flank from La Quiaca in the Andes all the way to Ushuaia & Tierra del Fuego in the Magellan Strait. The sky is a great dome, and in some sections only the odd far-off estancia breaks up the long horizon. And the road is a sight in itself: it careers through Andean switchbacks, passes from wide, open plains into narrow corridors of rock, and sometimes seems to disappear altogether into banks of cloud.

Is this drive for me? What to expect from the Salta–Mendoza section of Ruta 40

Driving the whole of ‘La Cuarenta’ (as it’s affectionately known) would take months, but you can still taste its wild, frontier-like feel in just five or six days by taking on almost a third of it. This is the 2,000 km (1,243 mile) section from the colonial city of Salta to Mendoza, the desert-oasis-like heartland of Argentinian viticulture.

This section of Ruta 40 darts and wiggles its way through a protean landscape that takes on many guises — sometimes it looks like the Valley of the Kings, sometimes Australia’s Red Centre. Geology is one of the route’s main calling cards, from Triassic badlands to a mountainside striped with rocks of green, yellow, red, brown, purple, white and pink. You’ll want to allow at least six days to make the most of it, adding on extra nights in some places.

The areas on the route receive few overseas visitors. As such, they’re often blissfully free from tourist trappings and the brute commerce of other parts of the country (I’m looking at you, Iguazú).

However, the price to pay for entering this undeveloped, sparsely habited realm is a lack of services in English. I strongly recommend you speak at least intermediate-level Spanish if you’re thinking about driving this route independently. The compulsory ranger-guides at Talampaya and Ischigualasto National Parks, two of the major archaeological highlights, only speak Spanish — so you might want to brush up on that palaeontology vocabulary, too.

The best option for non-Hispanophones wanting to experience this route is to travel with a driver and bilingual guide. It’s more costly, yes, but it gets around the language barrier and you can gaze out the passenger windows to your heart’s content.

Places to stay and facilities en route

Small towns of 200 or so inhabitants crop up occasionally along this section of Ruta 40, so you’ll always have some bastion of civilisation in which to spend the night (something I found unexpectedly comforting after a day’s driving through impassive, deserted landscapes).

These towns follow a soon-familiar blueprint, revolving around a main square, a church, a handful of shops and a fuelling station. Their range of restaurants isn’t great (think of them as pit stops), but they serve tasty enough meats and Italian dishes.

The hotels are mediocre, so I suggest bookending your trip with more elegant stays in Salta and Mendoza.

Highlights of the route

Salta to Purmamarca

You begin your journey by flying into ‘Salta the Beautiful,’ a two-and-a-quarter-hour flight from Buenos Aires. Its moniker becomes apparent when you enter the main square, Plaza 9 de Julio, which is lined with orange trees and candlelit cafés, and fronted by a cupcake pink cathedral.

You don’t need to spend long here before beginning the drive, but it’s worth ambling about for a day or so, admiring the many neoclassical buildings and visiting the MAAM (Museum of High Altitude Archaeology). Its key exhibits are some eerily well-preserved Inca mummies: sacrificial children, whose 500-year frozen state has left even their hair and nails almost perfectly intact.

Exploring the Humahuaca Gorge

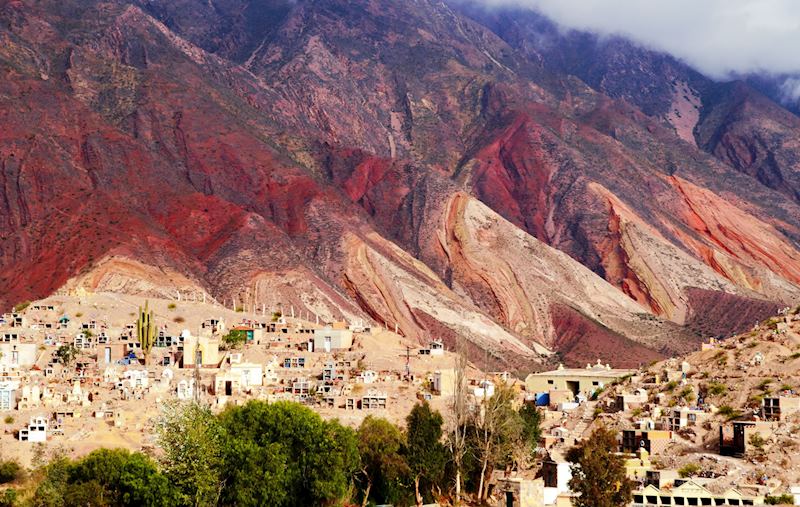

Your first day of driving is a leisurely three hours’ north past waving plains of grasses and mountain ranges stretching on into the far distance. You arrive in Purmamarca, a languidly paced town at the foot of one of the area’s geological supernovas: the Cerro de los Siete Colores (the Hill of Seven Colours).

This polychromatic mountainside, with its strata shades of sage green, buttery yellow, rose pink, oxblood and charcoal, is actually part of the colossal Humahuaca Gorge, a great cleft that runs north to south for 155 km (96 miles).

I recommend staying overnight and then spending a full day in the area, driving along the gorge floor to the mirador (viewpoint) looking over the Paleta del Pintor (Painter’s Palette), another mountainside on which bands of reds, oranges and whites run like seismic waves across the rock face.

If you can, make the 40-minute detour to El Hornocal, following a sinuous dirt track to a viewing point that gives you an even better prospect over the Paleta. At 4,300 m (14,100 ft) above sea level, the sky here is usually a clear, crisp blue, setting off the rich shades of the mountains even more.

You can also stop at small, whitewashed conquistador-era towns and settlements along the gorge. You’ll see coca tea and alpaca jumpers being sold, and catch snatches of Quechua. The atmosphere is far more Andean — closer to Peru and Bolivia — than Argentinian.

Purmamarca to Cachi

It’s time to head south. The drive to the adobe highland village of Cachi can be a long one (more than five hours), as you skirt past Salta and begin to take on rougher, gravel roads.

My advice is to take your time and just drink it all in: the cattle ranches, the fields of cacti standing to attention like foot soldiers, and the splashes of rust-red bare rock among the dun-shaded escarpments of the Nevado de Cachi range.

I’d spare some time to see the Salinas Grandes, salt flats that loom on the horizon as a sparkling, bright-white line (it felt to me like driving into a mirage). After a rest and lunch stop in the mining town of San Antonio de los Cobres, you can drive to the Cuesta del Obispo (Bishop’s Pass). I gasped on reaching its mirador, as I looked back over the chicaning route I’d taken to get there. The hillsides and mountains looked like huge folds in a piece of velvet.

Cachi to Cafayate

This drive takes roughly four hours. The arid landscape occasionally blooms with flowering agave plants and offers few signs of human habitation: hushed hamlets, goat herders, a roadside crucifix.

As you approach Cachi, the road enters the Valley of Arrows, a sandy stretch pierced everywhere with horizontal rock strata that look as if they’ve been fired into the earth at acute angles.

The vines of Cafayate’s vineyards gleam emerald green after all that Martian starkness. You can spend a contented few hours (or even a whole day) exploring this wine-producing town, popping your head into its different bodegas and sampling their torrontés wines (which make dry and sweet whites) as well as silky merlots and cabernet sauvignons.

Cafayate to Belén

The main event on this drive occurs early on, 40 minutes south of Cafayate. The pre-Columbian ruins of Quilmes form a private archaeological site named after an indigenous people who once thrived in this province. Similar to Inca settlements, it’s made up of mortarless stone terraces, part-fortress, part-housing, part-agricultural plots.

The Spanish rounded up the remaining Quilmes in 1667 and transported them to a reservation near Buenos Aires; today only a few descendants remain. Knowing this, the site can feel a little melancholy, deserted apart from the odd llama and watched over by candelabra-like cardon cacti.

It’s not unheard of to scuff the ground with your feet and turn over shards of pottery, or even an arrowhead. If you climb to the highest terrace, you’re rewarded with a bird’s-eye view over the site, framed by endless-seeming desert.

The rest of the three-to-four-hour drive takes you past dry riverbeds, scrubland singing with cicadas, and plains with views onto far-off, snow-covered mountains.

As you approach Belén, the scenery changes again on entering the Quebrada del Complejo Termal, a red sandstone gorge formed through geothermal activity.

Belén to Villa Unión

Don’t be disappointed by the first hour or so of this leg. Soon you’re into a stretch of well-paved cornice called the Cuesta de Miranda. It weaves between gorges, peaks, buttes, and startlingly bright red rock caused by iron oxide. You could even find yourself driving through wisps of cloud.

It’s like passing through a hybrid of several US national parks in mere hours: Monument Valley meets Arches meets Zion. It took me five hours to drive the Cuesta, which ends at Villa Unión — I was constantly stopping to take pictures, reaching the crests of hills and pulling over to look back on the road’s snaking progress. The landscape was devoid of any sign of humanity — I felt like I’d wandered back in time to the age of the dinosaurs.

Exploring Talampaya and Ischigualasto National Parks

Speaking of dinosaurs, I strongly suggest staying on in Villa Unión for an extra day, just so you can visit the nearby UNESCO World Heritage Sites of Talampaya and Ischigualasto National Parks. You explore them in convoys, driving from site to site, with ranger-guides. Despite being separated by little more than 50 km (31 miles), the two parks are strikingly different in landscape.

Talampaya is focused around an immense red sandstone canyon littered with surreal rock formations such as hoodoos, all given quixotic names (‘the Monk’, ‘the Mushroom’). Guided tours take a circuit around the park, showing you the most celebrated sites. The one that really sticks in my mind is ‘the Cathedral’, towering sandstone cliffs whose shape resembles the soaring piers of a cathedral’s nave. You might see condors overhead, and nandus (Argentinian ostriches) picking their way through the rocks.

Ischigualasto, in contrast, is dominated by a moonscape of greyish dust, which can look almost white when the sun shines brightly. Guanacos mill about listlessly. Dotted around this aptly named Valle de la Luna (Valley of the Moon) are petroglyphs and fossil sites whose remains have been instrumental in helping to trace the evolution of vertebrates.

My guide told me, with a visible glow of pride, about the finding of Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis. One of the country’s most significant discoveries, the theropod-like carnivore dates right from the end of the Triassic Period, making it one of the oldest specimens ever found. You can see fossils in situ around the park and exhibited in the palaeontology centre.

Villa Unión to Mendoza

Your final day’s drive takes about five hours, door to door. The scenery doesn’t quite outcompete what has come before, but after lunch in the nondescript town of San Juan your endpoint looms into view: the wine(ries) of Mendoza.

The town itself is leafy and cosmopolitan in feel, and fountain-filled (despite its desert location). Come evening, its bars and cafés brim with sophisticate revellers.

But I’d hold onto that feeling of seclusion, imbued by a journey through such remote and untouched lands, for just a few nights longer. You could stay 16 km (10 miles) outside Mendoza in the Posada Verde Oliva.

This boutique hotel lounges in its own vineyard in the Maipu Valley, and rooms have private terraces overlooking the manicured vines. There’s a small outdoor pool with sun-recliners, a bar, and the kind of creature comforts you appreciate after nights on the road: fluffy bathrobes and slippers, and massage treatments in the spa.

Perhaps best of all, you can walk out the front door and reach several boutique wineries within minutes for impromptu Malbec tastings.

Practicalities of driving Ruta 40 from Salta to Mendoza

- Don’t think about using anything less than a top-of-the-range 4x4: while roads are well-paved in some places, there are also numerous gravel and dirt tracks.

- Fill up your tank every time you stop for the night — you’ll be driving long stretches during the days, where fuelling stations are few and far between.

Best time to drive from Salta to Mendoza

Given the aridity of the landscapes you’re driving through, it’s best to avoid the Argentinian summer (December to February) and opt for springtime (September to November) or April and May. At these times of year, the temperatures are generally pleasant and there’s less chance of rain.

Start planning your trip to Argentina

Start thinking about your experience. These itineraries are simply suggestions for how you could enjoy some of the same experiences as our specialists. They're just for inspiration, because your trip will be created around your particular tastes.

View All Tours in Argentina